Oyler House, Lone Pine, 1959, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Hauptinhalt

Richard Neutra.

California Living

Neutra was impressed by the highly developed industrial production in the U.S., but was also simultaneously concerned with physiology, psychology, and behavioral research — aiming at a new, humanist architecture. His buildings are marked by open ground plans, light structures, and a close relationship to the surrounding landscape; they follow a strict system, yet at the same time, were tailored to the clients’ individual living needs.

Exhibition views, Wien Museum MUSA, 2020, Photos: Christoph Panzer

The exhibition is the result of a research trip by the two curators and approaches Richard Neutra’s life and work at two levels: the photos by David Schreyer present nine exemplary homes by the architect, which with their compact ground plans and clever space configurations, not only counter the cliché of Neutra as a builder of luxurious villas, but also offer viable role models for contemporary building.

Supplementing this is an examination of Neutra’s eventful relationship to Vienna, where he spent his formative years, and where he futilely longed to return at the end of his life.

The exhibition’s starting point is likewise its goal: to present the personal, onsite experiences through images that deliberately refrain from iconic staging, showing the uninterrupted—or new—topicality of Neutra’s architecture rather than celebrating him as a proponent of a nostalgic, commercial “midcentury modern” style.

Andreas Nierhaus and David Schreyer, Curators

Chapter 1

Nine

exemplary

homes

McIntosh House

Silver Lake, Los Angeles

1937–1939

Closed off and nearly inapproachable on the street side, the small house opens with a grand gesture towards the garden, which seems like an additional outdoor living space, bordered by a right angle, allowing the house to appear much larger than its actual 900 square feet. The construction is timber-framing clad with dark brown California redwood. The silver paint of the wooden window frames imitates steel constructions used by Neutra in more elaborate, contemporary building commissions. The buildings costs were a mere 3,800 dollars.

The actress, singer, and artist Ann Magnuson purchased the house in 1992. Her husband, the architect John Bertram, renovated several Neutra houses. The minimal size presents a challenge for both, because the formal stringency of the house also does not permit any disorder. On the other hand, they find its spatial economy and modesty liberating, as the house holds them back from collecting useless things.

Miller House

Palm Springs

1936–1937

The socialite Grace Lewis Miller wanted to offer exercise classes for women in Palm Springs and commissioned Richard Neutra with the construction of a home including a studio. After the Lovell Health House (1927–1929), Richard Neutra now once again had the opportunity to build a house exhibiting light and transparent architecture suitable for the new body image. Perhaps that’s why the Miller House became the most elegant structure that the architect was able to build in that period.

When Catherine Meyler purchased the house in 2000, not many of its design qualities were still recognizable. Through careful restoration of the artwork, Meyler, who mediates locations for film and photo shootings, succeeded in creating an atmosphere that is reminiscent of the 1930s yet does not seem museum-like. And she realized an addition already planned by Netura, which would now serve as a guest area. The new owner of the house was thereby able to fulfil one of the wishes of her predecessor.

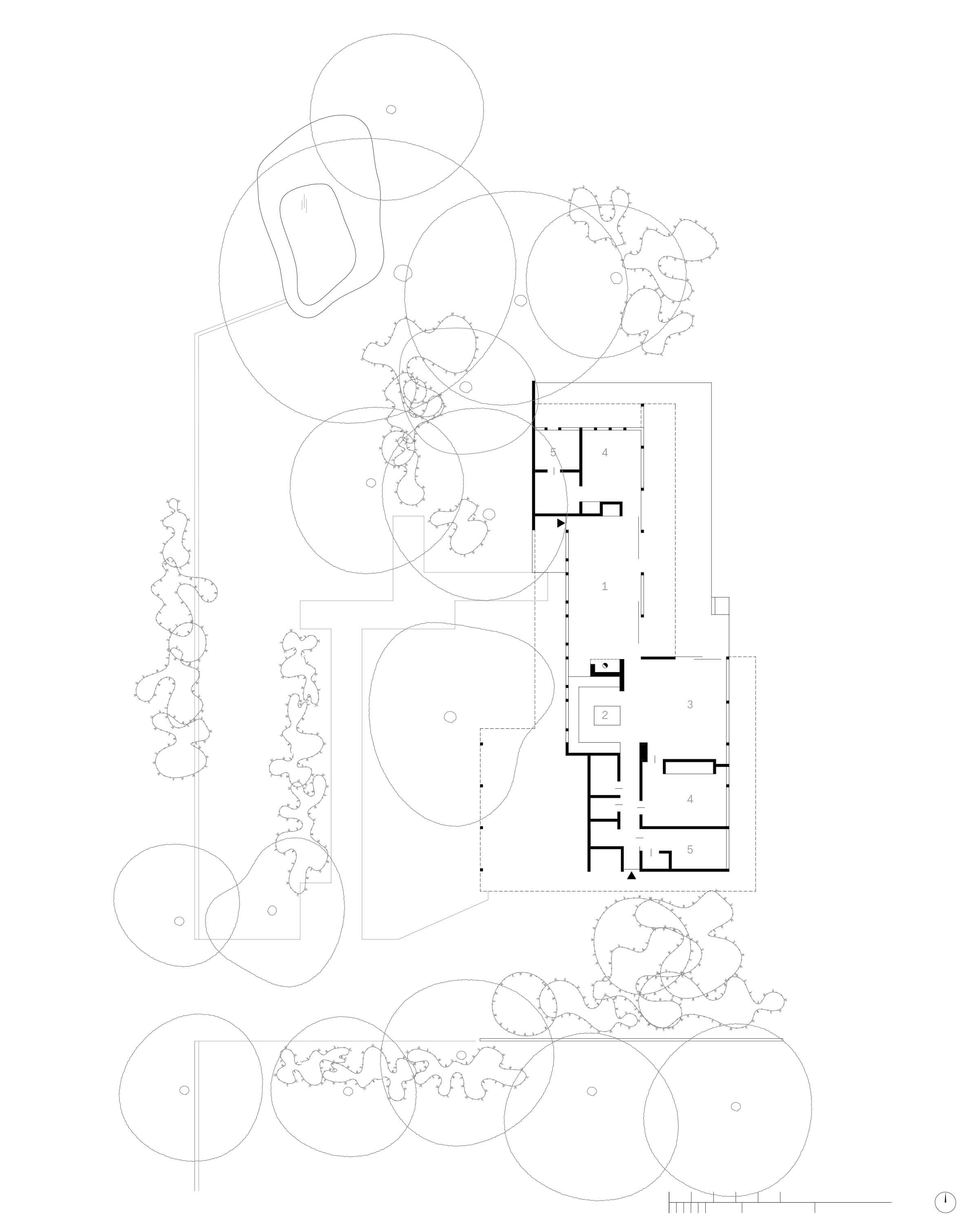

Oyler House

Lone Pine

1959

Lone Pine is located about a three-and-a-half-hour drive north of Los Angeles at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Richard Neutra built one of his most unusual houses here. The client, the official and insurance salesman Richard F. Oyler, had discovered the architect’s buildings in the local library. Neutra was used to working for clients with small budgets and designed one of his most impressive homes. The stones for the retaining wall were gathered on site, and Oyler worked on the wood balconies himself. The flat roof projects unusually far to shield the house and its inhabitants from excessive heat.

The actor Kelly Lynch and film producer and author Mitch Glazer purchased the Oyler House in 1992, years before the hysteria broke out over “mid-century modern,” and many of the couple’s friends couldn’t understand their choice. According to Kelly Lynch, due to its compact ground plan and the natural building materials, the house is a role model for today. It’s a work of art and at the same time, the best evidence that a work of art does not have to cost a lot.

Oyler House, Lone Pine, 1959, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Oyler House, Lone Pine, 1959, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Wilkins House

Pasadena

1949

Das von John Entenza, dem Herausgeber der Zeitschrift „Arts & Architecture“, 1945 initiierte Case Study House Program hatte das Ziel, dem Publikum mustergültige und kostengünstige moderne Wohnhäuser als Modelle im Maßstab 1:1 zu präsentieren. Nur ein Teil der bis 1966 entworfenen 36 Häuser wurde gebaut. Vertreter der jungen Architektengeneration kamen ebenso zum Zug wie Richard Neutra. Sein Haus #13 war laut den veröffentlichten Planungsunterlagen für eine Modellfamilie „Alpha“ konzipiert und sollte demonstrieren, wie sehr der Architekt auf die in Fragebögen und Gesprächen artikulierten Bedürfnisse und Wünsche der künftigen Bewohner einging. Tatsächlich hatten ihm Gordon und Mary Wilkins längst den Bauauftrag gegeben, als das Haus publiziert wurde.

Im Jahr 2000 wurden Stacey und Jeff Mann, beide arbeiten im Filmgeschäft, Eigentümer des Hauses. Es war von Vegetation überwuchert, das Innere durch zahlreiche Veränderungen entstellt. Nach der Restaurierung sollte Julius Shulman das Haus fotografieren. Da die Manns noch keine Möbel hatten, wurde es kurzerhand mit Filmrequisiten eingerichtet.

Freedman House

Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles

1949

On the steep coast high above the Pacific, Richard Neutra built a house for Nancy and Benedict Freedman, a successful screenwriting couple. A house on the water in two senses, as the axis leading through the living space connects the Pacific with the pool. The unbridled wildness of the sheer endless ocean on the one hand, and the domesticated water on the other, with the building, hardly more than a membrane, in between.

The current owners, Marty Longbine and her husband, the music manager Jeff Ayeroff, perceive this openness as a special quality. According to Ayeroff, the ocean view yields a different picture every day. For him it is “a simple house that looks at the ocean.” Peter Grueneisen carried out the most recent elaborate renovation and expansion. The result is an unusually “dynamic” house in which the past does not collide with the present, but instead, is experienced as a self-evident part of a specific tradition — perhaps the new Mediterranean culture imagined by Neutra.

Freedman House, Pacific Palisades / Los Angeles, 1949, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Freedman House, Pacific Palisades / Los Angeles, 1949, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Strathmore Apartments

Westwood, Los Angeles

1937

With the Strathmore Apartments, Neutra accomplished the feat of building a uniform group of apartments, which at the same time—supported by the green of the initially still barren courtyard—bore the character of individual homes and thus met the demand for “individualized” living without denying its systematic and rational underlying planning. The apartments, originally mocked as “fashionable architecture,” had prominent inhabitants right from the start, including the actress Luise Rainer; film director Orson Welles; John Entenza, editor of Arts & Architecture and founder of the Case-Study House Program; and Charles and Ray Eames.

In 2006, the designer Rebeca Mendez and publicist Adam Eeuwens moved in, although it took quite some time for them to see their home as their own property and no longer as a museum object. For the two, the Strathmore Apartments, with their spatial economy and simultaneous high-quality design, are a model for the future of residential living in Los Angeles.

Strathmore Apartments, Westwood /Los Angeles, 1937, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Strathmore Apartments, Westwood /Los Angeles, 1937, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Ohara House

Silver Lake, Los Angeles

1961

Rather than an idyllic lake, Silver Lake is a reservoir that was built in the early twentieth century to guarantee the water supply for the rapidly growing city of Los Angeles. Neutra had already built his home and studio on its shores in 1932. A colony of nine houses by the architect arose nearby between 1948 and 1961. Hitoshi and June Ohara were the descendants of Japanese immigrants. Neutra’s understanding of architecture and residential life had been decisively influenced by an early stay in Japan, and apparently, he particularly valued the collaboration with these clients. The center of the house comprises the living space, opened as greatly as possible to the outside and expanded by glass walls.

The designer David Netto currently lives in the house. He appreciates not only the connection of the house to the landscape, but also particularly the decency and humility of Neutra’s architecture.

Ohara House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1961, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Ohara House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1961, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Kambara House

Silver Lake, Los Angeles

1959–1961

The house for George and May Kambara was among the last in a colony of nine houses that Richard Neutra built on the shores of Silver Lake. The Kambaras were descendants of Japanese immigrants and had concrete ideas about the appearance of their house. Although it is a compact, block-like structure, the individual floors seem to float over one another like platforms. The sliding wall between living room and dining area yields generous visual links from the balcony through to the back-facing courtyard.

Currently, the architect Elizabeth Timme and actor Hank Harris along with their children live in the house, which has been preserved in its original state. Whereas Harris appreciates the house’s strong personality, Timme is challenged to object. As an answer to rapid gentrification, she is involved in community-based urban development and designs affordable residential homes, so-called “backyard homes,” for which enough space would be available also in Silver Lake.

Kambara House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1959–1961, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Kambara House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1959–1961, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

VDL II Research House

Silver Lake, Los Angeles

1965–1966

For himself and his family, Richard Neutra was first able to build a home and place to work, which was finished in 1932, through a loan from the Dutch industrialist Cees van der Leeuw (“VDL”). Neutra experimented here with living technology in a quasi “self-test.” After a devastating fire in 1963, his son Dion oversaw the rebuilding of the house.

It now belongs to the California State Polytechnic University in Pomona. The current residents are the architect Sarah Lorenzen and her partner David Hartwell, an animation designer. They run the house and make it publicly accessible. Hartwell especially appreciates the relationship to the outdoors, which nonetheless plays less and less of a role in California because people prefer to retreat to air-conditioned spaces rather than enjoy the Mediterranean climate. Hartwell wants cities to look at these houses as a policy: “There are forms of architecture that socially create stress, and others that do not.”

VDL Ⅱ Research House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1965/66, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

VDL Ⅱ Research House, Silver Lake / Los Angeles, 1965/66, Photo: David Schreyer 2017

Chapter II

Richard Neutra

and Vienna

Childhood in Vienna ca. 1900

Richard Neutra has a sheltered childhood in Vienna’s second district, Leopoldstadt. Among his earliest memories are his parent’s somber apartment furnished with cumbersome, old-fashioned furniture near the Augarten park. Decades later, in his memoir, he cites it as his personal starting point for a strict renewal of living along the lines of modernism: maximum opening to the outside, sparse, functional furnishings, liberation from the decorative excess of the Gründerzeit. His two much older brothers, Wilhelm and Siegfried, study medicine and mechanical engineering, and are key role models; while his sister Josefine, six years his junior, influences him with her artistic ambitions. He admires the special technical proficiency and precision of his father who worked his way up from apprentice to owner of a foundry. As a youngster, Richard feels especially comfortable in his father’s workshop. Perhaps this was the start of the immense technical interest that would distinguish Neutra as an architect.

Defining encounters

In the years around 1900, the dispute over the sense and possibility of a strict renewal of architecture is more passionate in Vienna than in any other city. Otto Wagner declares “modern life” as the starting point for design; the forms of the past should no longer shape the base for architecture, but instead: purpose, construction, and material. As professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, he passes on this doctrine to the next generation. The young Richard Neutra follows the debates around Wagner’s project for the Stadtmuseum on Karlsplatz as well as the scandal surrounding Adolf Loos’s building on Michaelerplatz. Parallel to his studies at the technical university, today’s TU Wien, Neutra attends Loos’s private Bauschule (building school), which influences him greatly and awakens his interest in the U.S. He discovers the oeuvres of Frank Lloyd Wright and Henry Sullivan. The relationship to his brother-in-law, the art historian Arpad Weixlgärtner, stirs Neutra’s great interest in cultural history, which will define his thinking about architecture.

War and collapse

In the summer of 1914, just a few weeks after the shots in Sarajevo, reserve lieutenant Richard Neutra is called to Trebinje in the far south of Bosnia Herzegovina. Shortly thereafter, the war breaks out. His most important task is to observe the movements of enemy ships along the coast. Since he is not directly involved in fighting, despite a daily life of deprivation, he has a great deal of time on his hands to think of the world and the future that lies ahead for him in the U.S. As Neutra would later report, it is the Monarchy’s multilingual army that makes him a cosmopolite. He becomes acquainted with the population’s misery, and also comes down with a severe bout of malaria. He experiences the collapse of the monarchy in a sanatorium in what is now Slovakia. With his last remaining cash, he sets off for Switzerland to regain his health in a convalescent home near Zurich. Here is where he meets his future wife, Dione Niedermann. In light of the difficult financial situation, a journey to the U.S. is still far in the future.

California Calls You

Neutra’s direct connection to America from 1914 on is Rudolph Schindler, a student of Otto Wagner, who had traveled to the U.S. shortly before the outbreak of war. The letters between Schindler and Neutra testify to Neutra’s curiosity and Schindler’s homesickness. After the collapse, Neutra reports on the catastrophic situation in Vienna and pleads urgently for information about American architecture. He beseechs Schindler, who was working for Frank Lloyd Wright at the time, not to return to Europe, and asks for details on immigration into the U.S. In 1920, Schindler asks Neutra to send copies of Otto Wagner’s publications, and also sends him the manuscript of Henry Sullivan’s “Kindergarten chats,” to search for a publisher in Berlin, where Neutra has meanwhile begun working with Erich Mendelsohn. Neutra does not have enough money for the crossing. In 1921, Schindler manages to convince Wright to invite Neutra to work on his projects for Japan, but two years would pass until Neutra boards a ship in Hamburg headed to New York in 1923.

How does America build?

Publications can decisively shape architect’s careers — hat applies to the distribution of photos of their buildings, as well as widely circulated books. In the late 1920s, Richard Neutra was well known in his hometown and in the German-speaking world not only as the creator of the Lovell Health House, but as the author of important books about U.S. architecture. Interest in the subject was keen: until this time, there was little knowledge in Europe about U.S. building techniques and practices. During his first years on the new continent, Neutra and his wife Dione co-edited the highly successful book, Wie baut Amerika? (How does America build?), and then published a second book about America in the prestigious “Neues Bauen in der Welt” series by the Schroll-Verlag in Vienna in 1930. With these two books, Neutra was recognized not only as the leading expert for American architecture, he was also soon considered the most important representative of “Neues Bauen” (New Building) in the U.S., even though he had built relatively little until then.

Projects for Vienna

While developing his career in California, Neutra maintains steady contact to Austria. Initially, the length of his stay in America is undecided; a return is still an option. But the working conditions in Austria and Germany are not inviting. The economic recovery after the collapse is again destroyed by the world economic crisis beginning in 1929. In Red Vienna, private residential building comes to a complete standstill, the city fathers enforce an architecture with conventional building techniques and traditional forms, which is the opposite of what Neutra hopes to achieve. Before his arrival in California, he participates in the competition for a new synagogue in Hietzing. However, his strictly cubist “functionalist” project has no chance. In 1930 he is invited by Josef Frank to participate in the international Werkbundsiedlung. The small house would remain the only building by Neutra in his former homeland.

Family in danger

While Richard Neutra enjoys great prestige as a busy architect in California in the 1930s, his family’s situation in Austria after the Anschluss in 1938 becomes extremely perilous due to their Jewish heritage. His brothers Wilhelm and Siegfried, both over sixty years old, are able to flee to exile in the U.S. His sister Josefine, on the contrary, remains behind in Vienna: she is married to the art historian Arpad Weixlgärtner and is thereby largely protected from persecution through his status as an “Aryan,” which places her in a “privileged mixed marriage.” Nonetheless, her status is extremely precarious and dependent on the despotism of the Nazi regime. Weixlgärtner attempts to obtain citizenship for his wife through testimonials from prominent Nazi humanities scholars. The couple is forced to leave their official residence and is accommodated in an “Aryanized” villa in Hietzing. After the liberation in 1945, a fire destroys their home, and all of their possessions are thereby lost. The Weixlgärtners subsequently move to Sweden.

A star of post-war modernism

Neutra’s light and transparent homes provide an appropriate framework for the deceptively idyllic notion of the white, American nuclear family in the post-war period. Their close relationship to the surrounding landscape can also be interpreted as an offer of reconciliation between human and nature following the horrors of the war. In Neutra’s “biorealism” concept, he placed architecture at the service of people’s supposedly irrevocable “natural” needs. Similar to a doctor, an architect should heal and prevent diseases, whereby Neutra had in mind — in his estate planning — not only individual owners, but also the entire population.

Thanks to Julius Shulman’s iconic photos, which were published in professional journals and home living magazines, Neutra’s architecture was now known throughout the entire world. In contrast to the global functionalism of Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, a European émigré on the East Coast, it stood for a specifically American, Californian modernism featuring a close connection to the local culture, landscape, and climate.

Architect of books

Magazines and books are key in the global dissemination of Neutra’s ideas: his built structures are located mainly in the far distant westernmost area of the U.S., and only very few who know of his private homes have actually seen them in person—thus rendering photographic documentation, representation, and distribution that much more important. Willy Boesiger, who published the complete works of Le Corbusier, also publishes Neutra’s oeuvre from 1951. Neutra’s theoretical ideas (Survival through Design, 1954) as well as his memoir (Life and Shape, 1962) are promptly translated into German. The three volumes published by the Alexander Koch publishing house, Mensch und Wohnen 1956, Welt und Wohnung 1961, and Naturnahes Bauen 1970, are meant to illustrate the “biorealism” concept; however, they are used mainly as a mere collection of role models for the fashionable “Neutra style” that unfurls in the 1960s, which is sharply criticized by the young avant-garde. Neutra’s final book, Bauen und die Sinneswelt, about his own house in Los Angeles, is published posthumously in 1977 in East Germany, once again displaying his global influence beyond ideological borders.

Attempt at a return

Although Neutra is given several commissions in Germany and Switzerland in the 1960s, the relationship to his hometown proves difficult. Granted, it is not necessary to first “discover” him, as it is for the architects driven out in 1938. On the contrary, people are proud of the world-famous Austrian. An exhibition is devoted to him at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) already in 1949, he is granted the Prize of the City of Vienna in 1958, and he is meant to build a culture village in Kierling in 1962; there is also talk of him designing the Austrian broadcasting’s regional studio in Salzburg.

Dione and Richard Neutra spend most of their time in Vienna between 1967 and 1969. He anticipates contracts, wants to coordinate the Forschungsgesellschaft für Wohnen, Bauen und Planen, and establish an international architect congress. In the end, the film Die Ideen des Richard Neutra is made, commissioned by the federal government. Neutra presents a rival for established architects, the younger architects see him as representative of the establishment. The Neutras retreat from this unfriendly atmosphere and return to Los Angeles, resigned, in 1969.

Chapter III

Richard Neutra

Biography

1892

Richard Neutra, the son of Elisabeth and Samuel Neutra, is born into a Jewish Viennese family on April 8th. Samuel Neutra owned a foundry in Vienna’s 2nd district, Leopoldstadt.

1902–1910

attends the Sophiengymnasium, a secondary school on Zirkusgasse in Vienna’s 2nd district.

1911

after one-year of military service, Richard Neutra begins his architecture studies at the Technical University in Vienna. After an interruption due to the war, he graduates in 1918.

1912

Neutra meets Rudolph Schindler, a student of Otto Wagner and travels with Sigmund Freud’s son Ernst to Dalmatia. In the autumn, he enters Adolf Loos’s private “Bauschule” (building school).

1914

in the library, Neutra discovers the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, which has a long-lasting influence on him and increases his desire to become familiar with the U.S.

1914–1918

during the war years, Neutra serves as an artillery lieutenant in the Balkans where he contracts malaria and tuberculosis. He realizes his first building, a tea house, in Trebinje (Bosnia-Herzegovina).

1919

during his convalescence in Switzerland, he meets his future wife Dione Niedermann. He works with the garden architect Gustav Ammann in Zurich and at the office Wernli & Staeger in Wädenswil, and participates in courses by Karl Moser at the Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule (ETH) Zurich.

1920

brief return to Vienna, works in a Quaker aid organization, then moves to Berlin.

1920–1923

works at the office Pinner & Neumann in Berlin, later with Heinrich Staumer. For a short time, Neutra is the city architect for Luckenwalde near Berlin, and subsequently, an assistant to Erich Mendelsohn.

1922

marries Dione Niedermann.

1923

Neutra travels alone to the U.S. and works briefly for C. W. Short and Maurice Courland in New York.

1924

birth of his son Frank Lloyd. Neutra works as a technical drawer in the office of Holabird & Roche in Chicago and meets Louis Henry Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. He moves with his wife to Wright’s studio house Taliesin (Wisconsin) and becomes his employee.

1925

the Neutras move to Los Angeles and live in the house of Rudolph Schindler. Intense occupation with the utopian urban design “Rush City Reformed.”

1926

birth of his son Dion. Schindler and Neutra collaborate in the competition for the League of Nations palace in Geneva.

1927

publication of the book Wie baut Amerika? (How America Builds).

1927–1929

building of the Lovell Health House in Los Angeles. Neutra achieved his breakthrough with this spectacular building, which was celebrated as the first mature example of the “International Style” in the U.S. In the following four decades, he would realize hundreds of projects for residential homes, housing estates, and public buildings in the U.S. and Europe.

1930

Neutra travels via Japan, China, the Indian Ocean, and the Suez Canal to Europa. Traditional Japanese architecture would leave a great impression on him. Meetings with Alvar Aalto, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier.

1930

publication of the book Amerika. Die Stilbildung des Neuen Bauens in den Vereinigten Staaten.

1932

participation in the exhibition organized by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock “Modern Architecture” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Building of the VDL Research House as his home and office. Opening of Vienna’s Werkbundsiedlung, which includes also a model house by Richard Neutra.

1939

birth of his son Raymond.

1943/44

Neutra works as head planner and architectural adviser for the government of Puerto Rico.

1944/45

president of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne).

1947

with the Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs Neutra realizes one of the most well-known single-family homes of the twentieth century. In the post-war years, his frequently published buildings become models for modern living throughout the world.

1948

a lecture journey brings Neutra back to Europe again for the first time in eighteen years.

1949

a Neutra exhibition takes place at Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts

1949–1953

office partnership with Robert Alexander.

1954

publication of Neutra’s most important theoretical treatise, Survival Through Design.

1955

the Neutra archive is established at the University of California, Los Angeles.

1962

publication of his autobiography Life and Shape.

1963

a fire destroys his home and studio in Silver Lake. During reconstruction, Neutra works closely with his son Dion, who is likewise an architect.

1966–1969

Richard and Dion Neutra form an office partnership. Richard and Dionne spend most of their time in Vienna in order to give their son greater freedom. Nonetheless, the plan to re-settle in Richard’ former home is unsuccesful. They return to Los Angeles.

1970

despite ill health, Neutra embarks on a series of lectures throughout Europe. On April 16th, one week after his seventy-eighth birthday, he dies of a heart attack while visiting the Kemper house in Wuppertal, which he designed.

Richard Neutra

California Living

13.02. – 20.09.2020

(16.03. – 28.05.2020

closed due to Covid 19)

Wien Museum MUSA

Felderstr. 6-8

1010-Vienna

12.654 Visitors

17 Guided Tours

Curators

Andreas Nierhaus

David Schreyer

Photograpy

David Schreyer

Exhibition architecture

koerdtutech

Exhibition design

Bueronardin